By now, most people who have not lived in a social isolation experiment for the last 50 years have

heard about the so-called “Mayan

Apocalypse,” the idea that, with the completion of the full cycle or “long

count” of the Mayan calendar on December 21, 2012, the world will end or be

transformed in some kind of catastrophe.

Exactly how the

world is supposed to end differs from account to account, as shown by the way

the theme has appeared in popular entertainment. The very last episode of the

television show The X-Files featured

a scene in which it was revealed that December 21, 2012 would be the date of an

invasion of Earth by extraterrestrial aliens (see screen shots from “The

Truth,” Season 9, Episode 19, broadcast 2002); as it happens, alien invasion is

a popular Mayan Apocalypse scenario.

|

| (The X-Files, "The Truth [Pt. 1]," 3:26 into the episode) |

|

| (3:56 into the episode; image reversed for readability) |

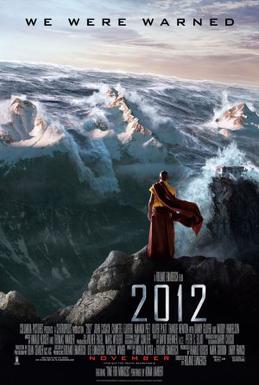

The 2006 movie 2012 posited that the increased solar flare activity during this“solar maximum” year would boil the Earth’s mantle, provoking mega-scale earthquakes and tsunamis (see poster, left, where a tsunami takes out a Tibetan Buddhist temple, hundreds of miles inland); this is another popular Mayan Apocalypse scenario. Other theories currently popular hold that the Earth will be demolished by a star / planet / comet / asteroid known as “Nibiru” on a very long orbit around the sun; claims about the Nibiru cataclysm are detailed in many YouTube videos.

On one level, the most important thing to know about this is

that there

is absolutely no basis in reality for the belief in the Mayan Apocalypse,

including the Nibiru cataclysm. This fact is the subject of a recent post

on the United States government’s blog, an extensive FAQ page on the

NASA website, a detailed article on

the website of NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center, and, according to an article

in The New York Times, a public

website of the Russian government. This is the subject of John Michael Greer’s

book, Apocalypse Not (see cover;

available through the widget above and to the right). The Nibiru cataclysm in

particular has been debunked thoroughly in two well-written YouTube videos by

“3WME” (available here

and here). (UPDATE: NASA has created a video, supposedly for December 22nd, which debunks the Mayan Apocalypse in less than four-and-a-half minutes. Watch it here.)

Put simply: no, the world is not going to end on December 21, 2012, and there is no reason to

think that the world will end anytime soon.

However, that is not

enough, for a student of psychology.

It is not enough to know that there is no basis in reality

for what can only be described as a mild social hysteria regarding the Mayan

Apocalypse (a hysteria that apparently has even driven some to suicide,

according to the Times). No, as

students of psychology, we must ask: Why

has this social hysteria occurred? Why is this notion so widespread? What

maintains this belief?

As it happens, different theories in personality psychology and cognitive psychology

have something to say about the psychological underpinnings of the belief in

the Mayan Apocalypse. Below, I give brief descriptions of how some of these

theories might approach this issue, roughly in the chronological order of each

theory’s emergence. (Note: these explanations are not mutually exclusive! And, yes, I know that I am applying

theories of individual personality and cognition to

the social realm.)

Freudian Psychoanalytic Psychology

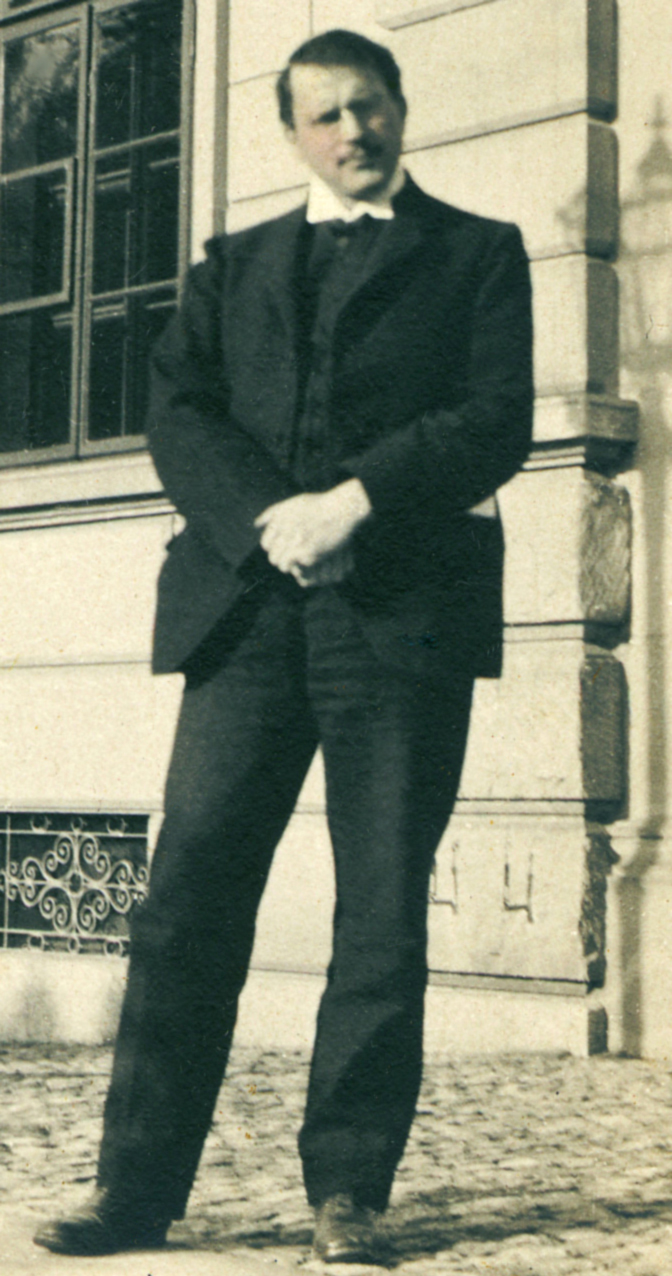

Beginning in his book Beyond

the Pleasure Principle (1920), Sigmund Freud (1856-1939, pictured) posited

that humans had a “death drive,” expressed in self- and other-destructive

impulses, expressed socially in war. Why this should be so would require a

lengthy consideration of Freud’s work (including Beyond the Pleasure Principle, The

Ego and the Id [1923], and Civilization

and Its Discontents [1930]—all written many years after Freud gave up

cocaine in 1896, for those who are wondering). In brief, part of the idea here

is that an organism seeks to discharge tension, and death is the ultimate

tension-less state.

The applicability to the Mayan Apocalypse is clear. The

world in the early 21st century, especially in the industrialized

countries, is heavily overstimulated with electronic media and the weight of

hyperconnectedness. In addition, the normal anxieties of life are amplified on

a global scale, what with concerns about multiple wars; the potential for

terrorist attacks (let alone their nuclear or biological variants); climate

change and its consequences (extreme weather, rising ocean levels); pandemic

disease. In a very broad-brush way, the end of the world would end the overstimulation, end the anxiety, end the tension:

Death, the great simplifier. I see this as a deeply deficient solution, of

course. But on a primitive level of the mind, perhaps it seems otherwise; the

Mayan Apocalypse would appeal to that primitive level of mind.

Jungian Psychology

Freud’s contemporary and one-time disciple, Carl Gustav Jung

(1875-1961, pictured), took depth psychology in a very different direction than

Freud did. In particular, Jung thought that humans were born with certain

fundamental cognitive structures, the archetypes—impossible to apprehend

consciously, but appearing in symbolic form in myths, dreams, and legends. One

such archetype is the Self, the apex of a person’s fully developed

individuality; it is often symbolized by circular objects, such as mandalas, or

spherical objects, such as the Sun. Another archetype is the Shadow, which

represents the traits one has that are not acceptable to society or to oneself;

it is often symbolized by dark and destructive beings or objects. (See Man and His Symbols by Jung and his

associates, an accessible—if unfortunately titled—introduction to Jungian

personality theory.)

In the language of the archetypes, the Mayan Apocalypse

represents a fear, and perhaps a warning. In many ways, the 20th and

early 21st centuries have shown humankind rather at its worst, in

terms of large-scale violence and oppression, environmental damage, and the commodification

of human life, that is, the reduction of everything to economic terms. (The recent

scandal involving a cover photo in the New

York Post—where the photographer apparently declined to save a man’s life

in order to photograph that man facing a subway train a moment before it killed

him—is an extreme example of this commodification.) The notion of the Earth (in

Jungian terms, a spherical symbol of the Self) being destroyed by chaotic

forces (in Jungian terms, symbols of the Shadow) is a sort of archetypal

nightmare. Having it clothed in the garb of Mayan myth (embodying another

Jungian archetype, the Old Man or Woman who bestows wisdom) would make this nightmare

all the more powerful.

The Nibiru cataclysm—where some celestial body, the agent of

chaos, literally comes out of the ‘Shadow’ of outer space to destroy the

Earth—is, if anything, even a neater archetypal nightmare in Jungian terms.

Jungian individuation—the process of becoming one’s best possible self, in a

sense—involves a “conjunction of the opposites” in which the Shadow becomes

reconciled to and incorporated within the Self. In the Mayan Apocalypse, the

Shadow demolishes the Self. As a vision of our potential societal future, the

Jungian reading of the Mayan Apocalypse obsession poses quite a serious warning.

No wonder these matters would be on society’s mind, from Jung’s point of view.

[Note: See what The Jung Page has to say about all this.]

[Note: See what The Jung Page has to say about all this.]

Humanistic Psychology

Humanistic psychology, as embodied in the work of such

psychologists as Rollo May (1909-1994, pictured), is concerned with how issues

of meaning, freedom, human connectedness, and mortality are worked out in the

life of the individual. In humanistic counseling and psychotherapy, dream analysis

concerns itself with how these themes expose themselves symbolically in the

life of the individual.

From this perspective, one can read society’s obsession with

the Mayan Apocalypse as demonstrating a fear that the world of the 21st

century offers little support to the individual when it comes to the weightier

matters of life. The decline (especially in Western Europe and some American

locations) of traditional religion leaves some people with little sense of the

greater meanings of life, yet “doomed to freedom,” in the phrase of Jean-Paul

Sartre (an existentialist philosopher, of some note among

humanistic/existentialist psychologists). I find it instructive that two recent

films—Melancholia (2011) and Seeking a Friend for the End of the World

(2012)—explore the meaning of human connectedness in the face of an inescapable

Nibiru-type cataclysm. And what better vehicle could one have than the Mayan

Apocalypse to force unresolved issues of mortality and life’s ultimate meanings

to the very forefront of our thoughts, on a planetary scale?

Cognitive Psychology

There are a couple of ways in which cognitive psychology

might be applied to society’s obsession with the Mayan Apocalypse, both of

which deal with why people might believe in ideas, like the Mayan Apocalypse,

which have such a poor body of supporting evidence.

First, one might consider the matter of systematic,

‘hardwired’ biases in cognition. The study of such biases was pioneered by the

psychologists Amos Tversky (1937-1996, pictured left) and Daniel Kahneman (b.

1934, pictured below left), as documented in their seminal 1974 paper, “Judgment Under

Uncertainty: Heuristics and Biases” (Science,

185, 1124-1131; widely anthologized).

First, one might consider the matter of systematic,

‘hardwired’ biases in cognition. The study of such biases was pioneered by the

psychologists Amos Tversky (1937-1996, pictured left) and Daniel Kahneman (b.

1934, pictured below left), as documented in their seminal 1974 paper, “Judgment Under

Uncertainty: Heuristics and Biases” (Science,

185, 1124-1131; widely anthologized).

Consider what Tversky and Kahneman labeled the availability heuristic: People consider

those things most probable that come to mind most easily. Hollywood has been

feeding movies about alien conquest of Earth into the public consciousness

since the 1950s; for recent examples, think of Independence Day (1996), War

of the Worlds (1953, remade 2005), Battle:

Los Angeles (2011), even Battleship

(2012)—this could easily become a very long list. Hollywood has also been

producing movies about global catastrophes since at least the 1970s; for recent

examples, consider The Core (2003), The Day After Tomorrow (2004), 2012 (2006), Sunshine (2007), and Knowing

(2009). Two major motion pictures about planet-killer asteroids hit the screens

in a single summer (Armageddon and Sudden Impact, both 1998), and in this

vein we should remember the aforementioned Melancholia

(2011) and Seeking a Friend for the End

of the World (2012). Global catastrophe is thus easily imaginable for

anyone who has been to the movies. This feeds into the bias of imaginability, one aspect of the availability heuristic:

that which is easily imaginable is considered all the more likely.

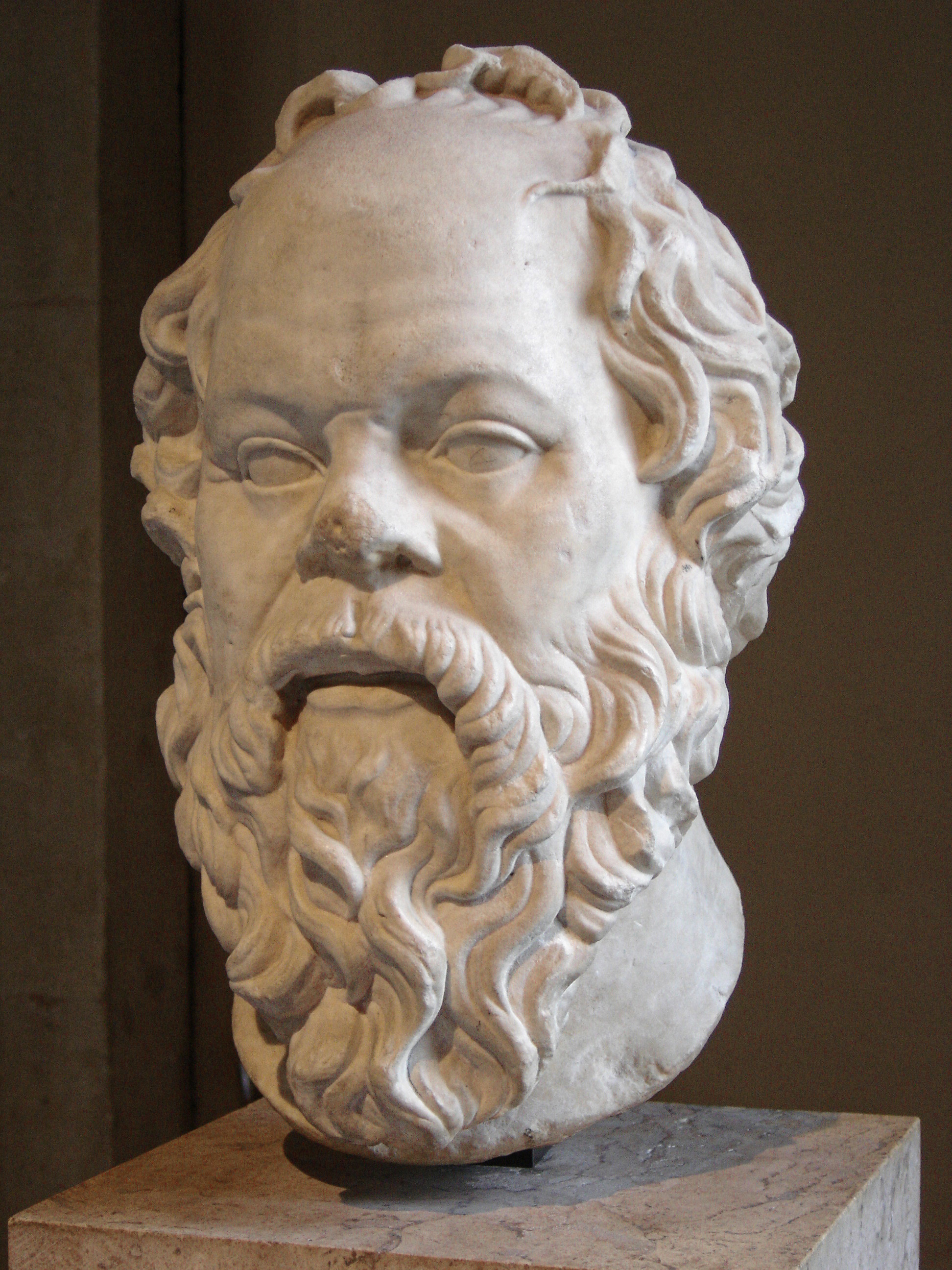

Second, one might consider the matter of critical thinking

itself. In a tradition going back at least as far as Socrates (5th

century bce, see bust),

philosophers have emphasized the need for vigorous testing of claims, to

explore the solidity of evidence and the soundness of logic—and, of course,

psychology as a discipline rose from within philosophy.

However, the literature and media (videos, etc.) that

support the idea of the Mayan Apocalypse utterly fail any standards of critical

thinking. (This topic would require an extremely long essay in itself.) In the

face of this, one has to wonder aloud what research might be constructed to

test for critical thinking skills, what programs could be devised to improve

them, and what program evaluation research might be applied to those programs.

(Students take note: There are many bachelors’ and masters’ and even doctoral

theses topics in here, I’m sure, not to mention an entire professional research

program for any enterprising psychologist.)

Transpersonal Psychology

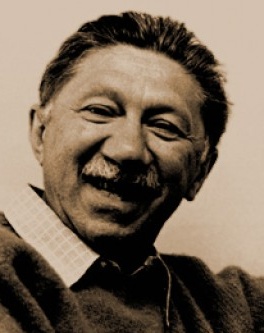

Transpersonal psychology was largely founded on the late

work of Abraham Maslow (1908-1970, pictured)—earlier a leading light of

humanistic psychology—who, near the end of his life, realized that

self-actualization was not the true top of the hierarchy of human motivations

for which he was famous: actually self-transcendence was. That is, when needs

lower on the needs hierarchy are met, people seek to connect up with something

greater beyond themselves, be that a Deity or Power, a cause, or the pursuit of

the Good, the True, and the Beautiful. (See my 2006

paper on Maslow and self-transcendence.)

From a transpersonal perspective, the societal focus on the

Mayan Apocalypse reflects a widespread inability to access the transcendent. To

put it bluntly, Western civilization is materialistic to a fault. In this

context, although people have an inchoate sense of a transcendent reality,

without a way to access that reality, they can conceive of it only in terms

that are utterly unreachable, even alien, chaotic, even malevolent. And, of

course, that is the Mayan Apocalypse: cosmic forces that are literally aimed at

Earth and result in its destruction. It is a vision of fear, borne of the

spiritually vapid nature of modern Western culture.

Conclusion

Before we can address damage—whether in the disordered

function of a patient or client, or in the fears or imbalance of a society—we

have to have a way of conceptualizing the problem. A brilliant psychologist and

mentor, Douglas H. Heath, once taught me to memorize this saying of Margaret

Mead: “A clear understanding of the problem prefigures the lines of its

solution.” Perhaps one of the personality theories above will give the reader

some insight into how to address our society’s issues, given that those issues

are manifest in such a phenomenon as the Mayan Apocalypse hysteria. Although I

have emphasized research in the Cognitive Psychology section above, in reality,

research may be conducted from within each of these perspectives. I wish student

theoriests and researchers well in addressing these issues.

Media may contact me through my website Contact page; I respond promptly.

Media may contact me through my website Contact page; I respond promptly.

Readers are welcome to comment on this post, below.

I invite you to become a “follower” of this blog through the

box in the upper-right-hand corner of this page, to be informed of future

posts.

Mark Koltko-Rivera on Twitter: @MarkKoltkoRiver .

The “Mark Koltko-Rivera, Writer” page on Facebook:

http://www.facebook.com/pages/Mark-Koltko-Rivera-Writer/13487584827

The “Mark Koltko-Rivera, Writer” page on Facebook:

http://www.facebook.com/pages/Mark-Koltko-Rivera-Writer/13487584827

[The opening image was found on the post

“Mayan Apocalypse?” of the blog SiOWfa12:

Science in Our World: Certainty and Controversy, the blog for a Fall 2012

course at Penn State University. The post was written by Nicholas H. Oliver; it

was unclear to me whether Mr. Oliver authored the image. The remaining images

are either in the public domain or are the property of their respective

copyright holders.]

Copyright 2012 Mark E. Koltko-Rivera. All Rights Reserved.